Framework for Application Security

- Introduction

- Business Case

- Definitions

- Risk Management

- Actors

- Activities

- FrAppSec Taxonomy

- Service catalog

- Putting it all together

- Supporting documentation and templates

- Useful and referenced links

FrAppSec or the Framework for Application Security is a model for the organization of a successful application security program at an enterprise level.

Introduction

Application security has evolved as a discipline and supporting function for application development over the past decades. The efforts for a consistent approach have usually been focused around the development lifecycle and have been less concerned with the overarching requirements and activities at an enterprise level.

The Framework for Application Security aka FrAppSec is a blueprint providing a holistic view of the application security landscape, identifying the actors involved in the process, their needs and ways to achieve those needs. The end goal is to deliver the acceptable level of security with the minimum amount of effort.

FrAppSec is also concerned with flexibility and provides a practical approach for smaller teams that want to deliver secure applications.

Over the past few years, application security started to get recognition as an independent and relevant discipline in the information security field.

ISC2 introduced a new domain as part of the CISSP certification called "Software Development Security (Understanding, Applying, and Enforcing Software Security)" accounting for 10% of the exam questions. CISSP is seen as one of the major certifications for information security professionals (e.g., Director of Security, Chief Information Security Officer) and the introduction of this individual domain is a reflection of the their agenda. The main topics for Software Development Security listed on their website are:

- Security in the software development lifecycle

- Development environment security controls

- Software security effectiveness

- Acquired software security impact

SANS and more recently the Center for Internet Security (CIS) included "Application Software Security" in their critical security controls list. The security controls list is a starting point for strategic security architecture roadmaps. It provides a generic prioritized approach and a dissemination of the controls into more actionable items. The scope of the Application Software Security control is to "manage the security lifecycle of all in-house developed and acquired software in order to prevent, detect, and correct security weaknesses". The nine sub-controls are:

- Patch management

- Application level firewall

- Input validation

- Automated security testing

- Suppression of error messages

- Separation of environments

- Hardening and testing in depth

- Security training for developers

- Suppression of development artifacts

The Building Security In Maturity Model (BSIMM) is a study of existing software security initiatives. By quantifying the practices of many different organizations, it describes the common ground shared by many as well as the variation that makes each unique. BSIMM is not a "how to" guide, nor is it a one-size-fits-all prescription. Instead, BSIMM is a reflection of software security. The aim is to measure and report the activities, not judge and propose models. All in all, BSIMM is structured in 4 domains, 12 practices and 113 activities:

- Governance

- Strategy & Metrics

- Compliance & Policy

- Training

- Intelligence

- Attack Models

- Security Features & Design

- Standards & Requirements

- SSDL Touchpoints

- Architecture Analysis

- Code Review

- Security Testing

- Deployment

- Penetration Testing

- Software Environment

- Configuration Management & Vulnerability Management

Other initiatives are also addressing aspects related to application security. One of the most notable is OWASP (Open Web Application Security Project). As the name suggests, the initial focal point was web applications’ security but the initiative grew over time to cover other aspects of the more general application security. According to their core purpose, OWASP is the thriving global community that drives visibility and evolution in the safety and security of the world’s software. There are numerous projects addressing various aspects, starting from documentation to technology and support for application security. The quality of the projects varies and further analysis is necessary in order to identify if the information is up to date or still relevant. The flagship projects are more reliable since they are usually funded and regularly maintained.

One of the OWASP flagship projects is the Software Assurance Maturity Model (SAMM), an open framework to help organizations formulate and implement a strategy for software security that is tailored to the specific risks facing the organization. It has a similar structure to BSIMM, 4 business functions, 12 security practices and 3 levels of maturity for each practice.

The examples above are a drop in the ocean of research, publications, tools and other elements related to application security. One can easily get diverted by the massive amount of available information and lose focus when building a consistent approach to application security. Paralysis by analysis becomes likely and can be followed by a tendency to over simplify or simply ignore the problem.

Certain patterns or recurring themes can be identified. While efforts have been made to build a one-size fits all approach, the reality is that particular situations require particular solutions which can in turn be based on more standardized but also abstract themes.

FrAppSec doesn’t hold all the answers nor is providing specific solutions. It aims to deliver the blueprint on which layers of abstraction can be disassembled to reach actionable items in order to achieve the end goal.

Pitfalls of the traditional approaches

The main pitfall of the traditional approach on application security is the lack of a consistent approach, doing whatever comes in hand and not having appropriate knowledge or proper understanding of all the aspects of an application. All the other pitfalls derive from this and it is a broader concept which is also applicable in other areas. Poor understanding of the problem will lead to poor decisions which will in turn propagate down the organization.

Some are considering penetration testing as being equal to application security. While it is a vital part of the application lifecycle, it is a process which is blind to certain aspects depending on the rules of engagement. It also comes too late in the application development process and therefore the cost of mitigation is high.

Application security budget increase is another approach which will not generate the expected results if it is not planned properly. As a business function, application security has to deliver the best return on investment for every monetary unit spent. Resources are necessary to deliver results, but how much is needed and how to distribute them is a byproduct of implementing a consistent approach like the one proposed by FrAppSec.

Focusing the investments around technology and neglecting the other aspects such as business goals, corporate culture, people and processes is not going to deliver results either. Buying expensive technologies without the knowledge of how to use them and lacking the manpower to operate those technologies is a dead end.

The automation of security testing is important for large scale implementations. However it must be seen as an initial activity in a maturity model and should not be used as the only way to assess the applications’ security. Depending on the risk profile of the application in question, manual security testing becomes a mandatory task. Automated tools detect only what they were programed to detect and do not provide sufficient testing coverage. They are usually unable to detect problems in the business logic and other multi-step attack vectors.

Snapshot security can also give a false sense of security. Annual audits provide a snapshot of the situation at a particular point in time and typically have a very limited coverage. Relying solely on these audits rather than a continuous process allows for extended windows of opportunities for attackers.

Trusting third party components by default is also a pitfall. Just because they come from a third party, it should not be assumed that they have a proper application security process in place. Open source libraries are a particular example of third party components which might be trusted by some because they have existed for a long time and are regularly updated. However this does not guarantee that security was ever considered. Building trust is a lengthy process and one that requires regular checks that the security bar is still at an acceptable level on the third party’s side. A third party able to deliver secure applications today might change completely in a year’s time.

Business Case

This section provides the elements needed to build a case for application security in an organization. It can be used as a foundation for application security managers to prepare for executive level talks. The readers are encouraged to look also for information within their vertical market and organizational culture.

Digital transformation is embraced by companies who want to stay relevant in the current economic landscape. The new constant is change and this is driving the agile approach to development of new business opportunities. Industries realized that they will no longer be relevant without leveraging the potential of new technologies.

We have to look no further than the Blockbuster vs Netflix case to understand the need for adoption of technology as an enabler to remain relevant in a changing market. Netflix started as a competitor to Blockbuster, renting hard copies via post but managed to leverage the Internet and the increasing bandwidth capacity, eventually taking their competitor out of the market. Digital markets are less stable than traditional ones and niche players can make a difference with limited resources. Disruption is the name chosen to depict the rapid paradigm shift.

The abundance and quick development of technologies is a blessing for adaptive organizations and a curse for traditional ones. This challenge was recognized by Gartner when coining the concept of Bimodal IT. This way, an established business can set a Mode 2 independent group to be less constrained by governance and more able to quickly react to changes in the environment.

At the heart of digital transformation lies the ability to process information efficiently. With Moore’s law losing relevance, the focus now is on building software to do more, create connections and learn unassisted from apparently dispersed data. Software became indispensable to our everyday life and increased productivity exponentially.

Software development emerged as a discipline and moved to become a major economic driver in just a few decades. Its amazing strength is the large availability of tools to build more software. Anybody can write software given the knowledge. In the physical world, one needs materials, tools and knowledge to build things. All these have been refined over centuries and unfit products in the physical world rule themselves out. This is not necessarily the case for software and it shows in the abundance of defects that software products are shipped with.

A particular set of software defects are the security vulnerabilities. What makes them different from other defects is that they can be abused by malicious actors for profit. We have seen examples of security vulnerabilities which not only reduced the value of the companies producing or using insecure software but, in certain cases, endangering the very existence of the business. Larger organizations have better resilience when faced with the exploitation of security vulnerabilities but the shareholders are not happy with the value reduction of their assets. The long term impact of a security vulnerability is the decrease of customers’ trust in the organization. One of the major themes of Digital Transformation is the Client Centric approach and thus a decrease of trust is an indication of failure to meet the business requirements.

When we’re talking about software, we’re usually referring to a set of instructions telling the hardware what to do. In a real world scenario, multiple sets of instructions are used to create a complex environment, an application, from which the an entity, end user or business, can benefit. The application is a much more complex ecosystem since it is dependent not only on the instructions but also on the environment.

Traditional organizations failed to accept application security as a major discipline in the same way that traditional companies failed to adopt new technologies. Treating application security the same way as network security is a flawed approach since the application environment is rarely under control. Another pitfall of the traditional approach is to approach application security solely from a compliance perspective. A soft approach of compliancy lacks the necessary means to check and enforce the technical controls of application security.

Most applications are not stand alone blocks but rather they depend on a multitude of interconnected applications to deliver the desired functionality. In an effort to simplify the architecture, development teams are relying on third parties to provide information and they treat them as black boxes. Black boxes might rely on other black boxes and so on, generating a very complex architecture for those willing to go into details. If the trust model between the boxes is overlooked, then the security level of the application is reduced.

The key application security challenge is to manage complexity. This is nothing new at the enterprise level, as other departments are facing the same challenge. Layers of abstraction must be built to offer relevant views to various actors and an overview for the upper management.

FrAppSec or the Framework for Application Security is providing a feasible approach for dealing with securing applications. It’s focal points are:

- Business case. What are the things that can be achieved with minimum investment and maximum velocity in order to match the risk appetite.

- Risk Management. A business conscious approach takes the risk appetite as a major enabler in pursuing business opportunities.

- Actors and Perspectives. Different roles in the organization need different views on application security for improved efficiency. Centralization of perspectives rather than stacking them up in a pyramid provides a better understanding of the application.

- Taxonomy. All elements of a functional ecosystem must be optimally interconnected. FrAppSec provides the blueprint for achieving this.

- Flexibility. Providing a framework that is customizable to fit small groups, enterprises, anything in between and all the possible combinations.

Definitions

This chapter is of importance because several ambiguities appeared over time in respect to how some of the terms are used. The following definitions and explanations depict the spirit in which they are used in FrAppSec.

Application

In the context of the current framework, an application is a set of digital instructions designed to perform a group of coordinated functions.

FrAppSec needs a unified definition to include all flavours of applications that are in the scope of the framework but also leave outside those paradigms which are not suitable. The term System was avoided as it usually goes beyond the digital boundaries and includes hardware as part of the concept.

In practice, defining an application and its boundaries is more complex as the application is evolving and merging with other applications to deliver ever more enhanced sets of functions. A good rule of thumb is to apply the divide and conquer algorithm until the application is reaching a manageable size and can be addressed within the limits of the framework and according to the maturity level of the organization.

Application Security

Application Security is the group of activities performed before, during and after the lifecycle of the application. As an enterprise program, application security is dedicated to managing the resources to perform the activities in an optimal fashion.

In a broader context, application security includes the paradigms and actors outlined in the FrAppSec Taxonomy.

Business Owner

An application business owner is the entity who holds the rights to run the application in an attempt to profit from the successful operation.

Individuals are preferred over group ownership as they will have to sign for risk acceptance.

Not that the profit is not always monetary, an example would be the business support applications like an office suite which don’t generate financial value directly.

Security Champion

Security champions are the satellites of the Information Security function in other departments. They are active members of their departments, acting as subject matter experts in security related issues.

Security champions can and should be found in both non-technical (business) teams as well as in the technical implementation teams. They are usually hired by the department in which they activate and have a percentage of their time allocated to the security agenda.

Application security audit

An application security audit is a measurable and repeatable technical assessment of the application’s security against a specified baseline.

Traditionally, the application security audit is perceived as a non-technical compliance check.

It’s important to have a strict rule set around audits including:

- The scope

- Methodology

- Standard output (like reporting)

- Clear baselines (standards, best practices)

- Timeframe

- Observations outside the scope of the audit but with an impact on the outcome (blockers)

Static analysis

The practice of analyzing the source code of the application in order to identify potential vulnerabilities.

The activity is usually conducted with the help of automated tools and the results are manually reviewed. It can and should be integrated as part of the continuous integration pipeline, defects must be triaged, tracked and fixed.

Dynamic analysis or Penetration testing or Pentesting

Dynamic analysis is a runtime simulated attack on an application that aims to identify and potentially exploit security weaknesses, with the goal of gaining access to the application’s functions and data.

It can be automated, manual or anything in between. Depending on the information that is provided to the expert performing the activity, it can be white, grey or black box.

A white box approach means that the expert gets everything, from documentation to access to the infrastructure. He can conduct interviews with the actors involved to understand the functionality of the system and find flaws in the operating processes, not just on the technology side. The white box approach is highly desirable but not always feasible.

In a black box approach, the expert gets the minimum necessary information to isolate the scope. It is perceived as a real world type of exercise. It’s far less efficient that the white box approach as the expert has to spend time gathering information.

Most of the dynamic analysis is a shade of grey box testing. The rules of engagement are important to maximize the return on investment and focus the attention on the important items. At a minimum they should include:

- A clearly defined scope

- Contact people

- Communication protocol

- Clear authorization for the analysis

- Timeline

- Generic methodology

- Particular methodology to match the scope

- Generic checklist against standards and/or best practices

- Particular focus areas

Risk Management

Risk management as a broader concept is the identification, assessment and prioritization of risks followed by an economical application of resources to minimize, monitor, and control the probability and/or impact of unfortunate events or to maximize the realization of opportunities.

Risk management’s objective is to assure uncertainty does not deflect the endeavor from the business goals. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Risk_management)

Risk appetite is the level of risk which an organization is willing to tolerate.

For application security this means that a successful program must measure the risk posture of applications and, if need be, apply controls to reduce the risk to an acceptable level.

Risk calculation

When measuring risk, it’s important to differentiate between several concepts which might seem related, but they reflect different aspects.

Application criticality

Application criticality provides the business context and is an indicator for application security spendings. It can be expressed in absolute terms or relative to the other applications. Without this context, all applications have the same importance in the face of the auditor, thus they will get an equal share of the resources. This situation is unlikely and resources must be spent in order to provide the best return on investment.

The business owner is responsible for providing this figure which is a variable for the risk calculation formula.

One way of determining the application criticality is to look at the revenue or profit generated by that application. This is not always correct, as some applications might not generate revenue but support other applications that do so. Also, strategic applications might not yet be profitable during the initial iterations but are still critical for the success of the business.

The security function must align with the business owners and upper level strategy staff in order to determine this scale which is critical for the success of the application security program.

A sample application criticality scale in absolute terms:

| How important is the application for the business? | Score |

|---|---|

| Very important | 3 |

| Important | 2 |

| Not important | 1 |

Once the absolute terms have been determined for all the applications, a relative scale can be computed. Here is an example:

| Application | Absolute criticality (e.g. a maximum score of 10) |

Relative criticality |

|---|---|---|

| App1 | 9 | 100% or 1 |

| App2 | 7 | 77.7% or 0.78 |

| App3 | 3 | 33.3% or 0.33 |

In an established enterprise, the applications’ inventory and criticality is maintained by an enterprise risk management function. A less established environment can create the processes in order to map the applications for inventory and calculate the system criticality based on interviews with the business owners.

Traditional vulnerability risk scoring

An application vulnerability is a flaw that could be exploited to compromise the desired secure state of the application. Vulnerabilities are identified during the activities performed throughout the lifecycle of the application.

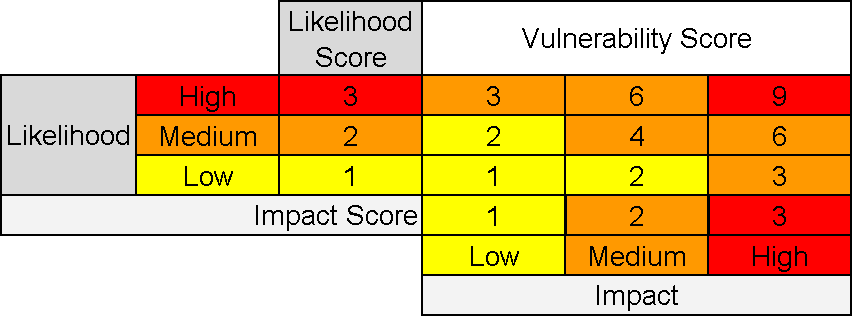

The risk associated to a vulnerability is expressed as the product between the likelihood of exploitation and the impact following a successful exploitation of that vulnerability.

Vulnerability Risk (VR) = Vulnerability Likelihood (VL) * Vulnerability Impact (VI)

A sample vulnerability risk scoring matrix with a scale of 3 for likelihood and impact:

Color coding is used in conjunction with the risk appetite statement to illustrate the zones which are not accepted.

Vulnerability risk scoring in the business context

The traditional approach of risk calculation lacks the business context. Consider the exact same vulnerability affecting a business critical application on one hand and a sandboxed test environment application on the other. The business will be far more interested in fixing the business critical application vulnerability if it is outside the risk appetite.

Efforts have been made to include this factor in the impact element of the traditional risk calculation formula. However it is a forced approach and most of the times the auditor is blind to the business context.

A better vulnerability risk scoring formula includes the relative application criticality (RAC) of the application which can be easily passed to the auditor or applied afterwards.

Considering the above application criticality scale, we can derive the relative application criticality needed for the formula.

| How important is the application for the business? | Score | Relative application criticality |

|---|---|---|

| Very important | 3 | 1 |

| Important | 2 | 0.66 |

| Not important | 1 | 0.33 |

The formula for vulnerability risk scoring calculation is now:

This formula addresses the problem presented above. The exact same vulnerability will have different scores depending on the relative application criticality (business context) and will be addressed differently.

It’s useful to create separate risk scoring matrices for each level of relative application criticality.

Application risk score

Once all the vulnerabilities have been identified an overall application risk score (ARS) can be calculated as the sum of all the individual vulnerability risks (VR).

If color coding is used for vulnerability risk scoring, the application risk score will have the highest vulnerability risk color code.

The application risk score tells two things:

- The total amount of risk for a particular application

- The highest level of risk for any particular vulnerability

Thresholds can be set for both indicators in terms of risk appetite. For example an enterprise might not accept individual vulnerabilities above a certain score. On the other hand, if an application doesn’t have any vulnerability with a risk above that level but has too many vulnerabilities below that risk score, a threshold can be set for the total amount of risk which must be met by the application.

Risk appetite

Risk appetite is the level of risk that an organization is prepared to accept in pursuit of its objectives. For application security, risk appetite statements can be prepared for three situations:

- Individual vulnerabilities

- Example: The organization does not tolerate any vulnerabilities with a score higher than X

- Application risk score

- Example: The organization does not tolerate applications with a total risk score higher than Y

- Enterprise application risk score (the sum of ARS of all the applications)

- Example: The organization does not tolerate an aggregate enterprise risk score (the sum of all the application risk scores) above Z

Prioritizing mitigation work

Prioritizing the order in which vulnerabilities are mitigated is guided by the risk statements.

For individual vulnerabilities the situation is straight-forward, all vulnerabilities with a risk score above the appetite must be fixed.

In case the application risk score exceeds the risk appetite but no individual vulnerabilities are above the previous risk appetite statement, a top-down approach is recommended, fixing the vulnerabilities with the highest risk score. Another approach is to have a good relationship with the development and business teams in order to identify the vulnerabilities that are most cost-efficient to mitigate while still managing to meet the risk appetite statements.

Production and development applications

When assessing application risk, the applications can be in two stages: production and pre-production.

For pre-production applications, the policies and procedures can prevent the application from making it to the production environment until the risk is below or equal to the organizational appetite.

For applications which are in production, the policy or procedure must specify a deadline for mitigation.

A sample situation where the risk is expressed on a scale of three:

| Vulnerability Risk | Time to mitigate (production applications) |

|---|---|

| High | 5 days |

| Medium | 30 days |

| Low | Risk accepted |

Actors

This chapter aims to identify the important individuals or groups who are involved in application security. These are not all the actors and depending on the organizational structure others might be identified. Clearly identifying the actors and their responsibilities is necessary to build a functional RACI matrix and the framework processes.

Chief Executive Officer - the head of the business is ultimately responsible for risk, including information security related risks. He or she needs to be informed on the aggregated risk of applications and consulted whenever risks are above the enterprise appetite.

Application Business Owner - the most senior business role involved in the application lifecycle. This individual is able to make critical decisions within his or her mandate in respect to information security. Clear identification of this role for every application is crucial in respect to risk acceptance and go / no-go decisions.

Data owner - the individual responsible with the ownership of the information processed by the application. This actor is responsible for creating and monitoring the roles and permissions which grant access to data.

Project manager - the organizer. Making sure that all the actors are synchronized and aiming towards a common goal. With respect to application security, the project manager makes sure that there are no blind spots in the process and the security team is aware and prepared to support the development efforts. The project manager must be trained in the process of application security and involve the relevant parties at the proper time. Maintaining the security calendar is also a part of the project manager’s role.

Architect - comes in several flavors: business, enterprise, domain, solution, security, etc. The IT Architect is combining Information Technology resources to meet business requirements. Depending on their role, they view the application from a different perspective. At each layer, fundamental security principles, generic security requirements and specific technical requirements must be known, understood and applied. The security architect is usually operating at an enterprise and not on an application level. However he can provide guidance for the other architects to make sure that security is embedded in the application and not added as an extra layer.

Developer - the actor in charge of building the application. A traditional view of the role would point out that the actor is responsible for writing code. In today’s world the developer has more attributes, which can include among others deployment and operations. This is the role ultimately responsible for producing secure code.

Auditor - in charge of checking the compliance. The auditor has a compliance list to check against. Can be technical or non-technical (list checking).

QA Tester - testing the functional requirements. All the functional security requirements can be tested during the QA phase. Criteria for non-functional requirements can be set in order to derive specific tests that can be performed by QA specialists.

Head of Information Security (CISO / Director / Manager) - the leading role of the information security department. In charge with the strategy for application security, responsible for the necessary policies and procedure, taking care of the obtaining and distributing the resources.

Security Tester / Penetration Tester - the technical actor in charge of identifying vulnerabilities. The security tester must act structured and procedural within the time constraints that apply for a particular test.

Security Champion - this actor is usually part of the development team, has been identified through training or other means and is showing a genuine interest in information security. The security champion is in charge of relaying the messages between the information security department and the development team, both ways. He acts as the point of presence for the information security department within the development team. A formal designation and recognition of the role and time allocation for security specific activities is needed in order to empower the security champion to act on behalf of the information security department.

These are not all the possible actors and depending on the particularities of the organization more or less actors will be involved in the application security process.

Dealing with too many actors might be an overhead so we can group them based on interests:

- Executives - defining the strategy and owning the risk

- Architecture - transforming the business strategy and describing the technological functions to achieve the goals

- Development - building the applications that are supporting the strategy based on the instructions provided by architecture

- Security - an overarching group whose goal is to make sure that the applications supporting the business strategy are meeting the risk appetite

Just like with actors, the groups can be defined depending on the particularities of the business.

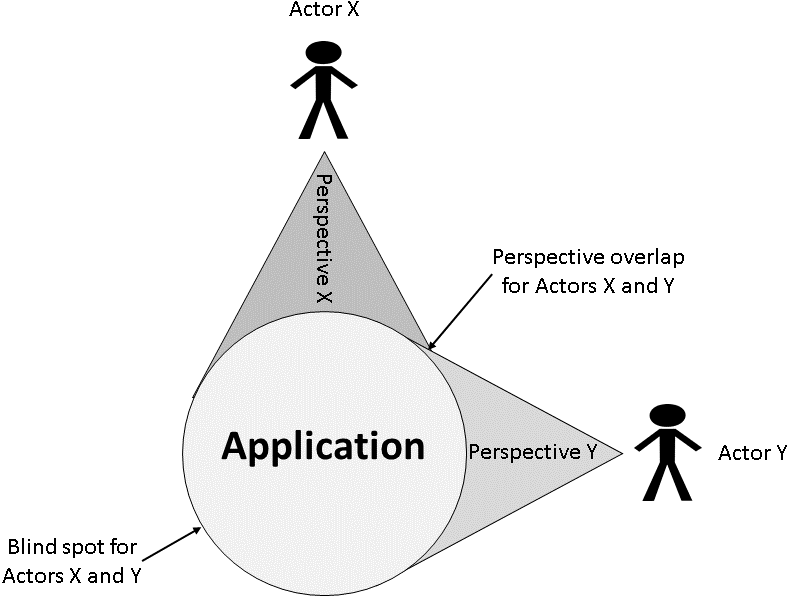

Perspectives

In the spirit of the current framework, a perspective is the point of view of a particular actor. Multiple actors will see the same application in different ways, will perceive certain aspects and be blind to others.

A successful application security framework is able to collate all perspectives in order to provide a holistic view, understand each actor’s needs in respect to security and provide the optimal solutions within the risk appetite. An ideal framework aims also to minimize the overlaps.

The way to achieve this is to ask each actor the right questions:

- What - the application

- Why - the motivation

- How - the processes

- Who - the people

- Where - the geographical considerations

- When - the timeline

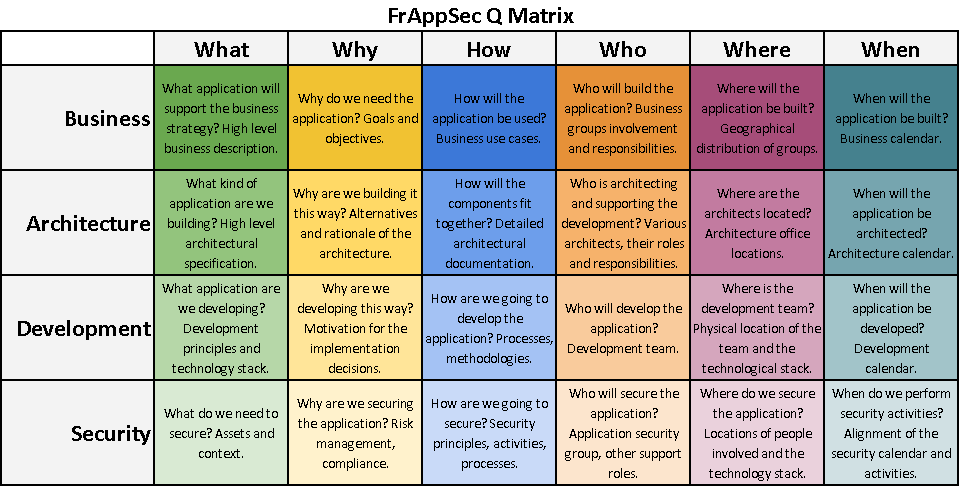

FrAppSec Q Matrix

For simplicity, the framework is providing the Q(uestions) Matrix as a mean to collect information focusing on the four actor groups identified in the previous chapter. A successful matrix is one that minimizes overlaps whilst avoiding blind spots.

In the spirit of the framework, the matrix is flexible and will be defined on an individual basis.

For established organizations and large application projects it makes sense to build a full Q Matrix adding the relevant stakeholder groups and asking all the questions. In such a situation, each answer might be more elaborate (an entire document) that can be attached to the matrix.

A small team developing one application in a startup fashion can reduce the size of the matrix on both dimensions. Most likely the business stakeholders are also acting as architects and even developers of the application. As a rule of thumb, the minimum number of stakeholders should be three, with Development and Security being mandatory. The other dimension can also be reduced. For example, small teams working in the same office without a geographically distributed technological stack can eliminate the "Where" column.

The Security stakeholder in the Q Matrix should be a reflection of the other ones. The matrix provides visibility and alignment between stakeholders and allows for gap identification in the initial phases of the project. Not only Security can benefit from having such a mapping.

FrAppSec Q Matrix is to be completed as part of the hard layer, during the customization of the intelligence group of activities in the maturity model. It is a specific document or set of documents for individual applications. It might not make sense to have a full matrix for all applications and this should be documented in the service catalog.

Activities

The scope of FrAppSec is not to detail the activities. Other initiatives ( BSIMM and OpenSAMM in particular) already did this and they have been through a number of iterations, making them mature and robust. FrAppSec aims at providing the interconnection between the activities in order to achieve a successful application security program.

In alignment with BSIMM and OpenSAMM, FrAppSec defines 4 areas and 12 activities that constitute the core of the application security program. FrAppSec is not debating the maturity model but is rather interested in the overarching taxonomy of the activities. A brief description is provided for the activities to better explain the connections between them and the way they should be understood in the current context.

- Governance - Organization, management and measurement of application security

- Strategy - defining the mission, roles and responsibilities, high level processes

- Define, track and categorize the scope (all applications)

- Define and publish processes

- Integrate with the processes to provide security and privacy sign-off

- Promote the existence and role of the security group

- Identify and collect metrics

- Track the security status in a unified manner

- Policy - collecting requirements and publish the top level policy and the associated processes

- Unify regulatory pressures

- Create secure development policy

- Perform data inventory based on data classification

- Align 3rd parties with the internal privacy and policy program

- Improve policies based on the feedback from the development lifecycle

- Training - providing targeted training for all the stakeholders

- Provide generic training

- Provide specific training

- Use internal, real world examples for training

- Execute hackathons

- Strategy - defining the mission, roles and responsibilities, high level processes

- Intelligence - Collection of knowledge to guide the secure development cycle

- Requirements - creating generic and specific requirements derived from the regulatory and strategic specifications

- Publish security standards and requirements

- Translate compliance in security requirements

- Create standards for technology stacks

- Identify and control open-source risks

- Features - building a set of standard features, customizing based on needs, guiding the reuse of secure blocks

- Publish security features and patterns

- Review the architecture of new features

- Establish a list of pre-approved, secure by design framework

- Attacks - inventorying data according to classification, building a list of common attacks, using real world events to enhance

- Map potential attackers

- Build attack patterns

- Publish real world attacks

- Develop new attacks

- Requirements - creating generic and specific requirements derived from the regulatory and strategic specifications

- Secure Development - Activities to be performed during the development life-cycle

- Architecture Analysis - reviewing the specific Intelligence items, standardizing architectural descriptions and analysis process, creating checklists for testing

- Review the architectural documentation

- Review data flow diagrams

- Log security defects in a unified repository

- Standardize architectural descriptions

- Create new security features and patterns

- Static Analysis - running manual and automated source code security specific analysis

- Perform automated code reviews and manually filter the results

- Enforce coding standards

- Log security defects in a unified repository

- Integrate static analysis in the development pipeline

- Customize automated static analysis rules

- Dynamic Analysis - performing manual and automated runtime security specific analysis

- Include basic security testing in the QA process

- Perform automated dynamic analysis and manually filter the results

- Perform manual testing

- Log security defects in a unified repository

- Perform testing based on requirements and features

- Integrate dynamic analysis in the development pipeline

- Architecture Analysis - reviewing the specific Intelligence items, standardizing architectural descriptions and analysis process, creating checklists for testing

- Production - Configuration, maintenance and monitoring of the application ecosystem

- Vulnerability Management - running continuous automated testing on the production environment, feeding the results back into the cycle

- Perform automated scans of the supporting infrastructure and manually verify the results

- Log security defects in a unified repository

- Automate and run the assessments periodically

- Use external partners to run black box hacking exercises

- Hardening - providing secure default states for the ecosystem, reacting to Intelligence changes

- Use an application layer firewall

- Implement standard security guidelines for infrastructure configuration

- Operational Intelligence - gathering feedback from operations and provide knowledge back into the cycle

- Implement a security incident management plan

- Implement technical means to detect security events

- Log security defects in a unified repository

- Use the intelligence gathered to feed the product life-cycle

- Simulate attacks

- Vulnerability Management - running continuous automated testing on the production environment, feeding the results back into the cycle

Even though FrAppSec is not addressing maturity levels, they must be considered for all the activities, aligning with the ITIL principle of continual service improvement.

FrAppSec Taxonomy

The taxonomy of activities, actors and paradigms provides the blueprint of FrAppSec. The paradigms introduced by the taxonomy are:

- Applications - the entire pool of the organization’s applications in the scope of the security program

- Application - an individual instance of the Applications paradigm

The connectors starting and ending points are important. Elements are grouped and connections can start or end either in a group or in a particular element. For example, the Intelligence activities are grouped and the entire group is specific for an application and generic for all the applications. The Training activity is for all the actors while only Executives dictate on Strategy.

The taxonomy is a blueprint. It does not depict all the elements nor all the connections between them. Activities, actors and paradigms can be added or removed according to organizational needs. The blueprint serves as a base for customization. It is a live document both from a framework perspective and also from an organizational implementation point of view.

Layers

The taxonomy has three distinct layers.

The Soft Layer revolves around the Governance and Intelligence groups of activities and apply to the Applications paradigm. It is the basis for the other layers and includes the generic documentation projects outlining the strategic approach on application security. The better and more comprehensive this layer is, the less work is needed for customization of specifics for each Application.

The Hard Layer encompasses the specific Intelligence items which are derived for an individual Application and the Secure Development activities. This layer deals with the technical aspects of developing a secure application.

The Real World Layer is about the production ecosystem. Once the hard layer delivered the application, the real world layer is responsible for security.

The Layers diagram is an abstraction of the general taxonomy, depicting the applicability of certain areas on the paradigms of Application and Applications. It is useful for determining functional zones, determining organizational structure and relationships. Communication between layers is ensured by the taxonomy, functional process are necessary for optimization.

Organization

An abstraction of the Layers diagram is useful for providing an organizational overview of the Taxonomy.

While the Soft layer needs Technology as much as the Hard and Real World layers need Processes, it’s clear who is the major enabler and driver for each layer. People are involved in all the layers.

Service catalog

Having a complete activities or service catalog is a must for a mature application security initiative. Applying the service catalog to individual applications must have a business context. Treating all applications equally can have two unwanted consequences:

- Overspending of resources

- Proportionality is not assured in respect to criticality

Budget driven decisions are to be avoided. A statement saying “we can spend that much on security for that application” is not going to produce the optimal ROI or assure proportionality.

The decision of customizing the service catalog for categories of applications should be driven by the risk appetite statements and the application criticality definition and inventory.

Risk identification happens in the Hard and Real World layers. Depending on the maturity level of the activities, more or less risks will be identified. If more resources are invested there is a higher likelihood of finding more risks, thus increasing the application risk score. Applying a certain level of services is a byproduct of applications’ inventory and categorization according to criticality which ensures business alignment.

The maximum service catalog is defined as the top level services that can be offered according to the maturity level for each activity.

The focus in creating the service catalog should be around defining the minimum catalog as a baseline to tackle all applications. Everything that can be automated and require minimum resources after the initial setup must be automated and included in the minimum service catalog.

Examples include:

- A strong and well documented soft layer can minimize the customization of the Intelligence items which are part of the Hard layer.

- Running static and dynamic automated security analyzers, defining the risk acceptance policy and feed the defects above the risk appetite automatically into the bug tracking system

- Performing vulnerability management on the entire infrastructure and at the application level if automation is possible

A proposed minimum service catalog can include:

- Generic non-technical training outlining the security principles, to be delivered as part of the on-boarding process and on a regular schedule afterwards

- Standard application security requirements

- Standard application security features

- Automated source code security scanning

- Automated penetration testing

- Vulnerability assessment for the production environment

The service catalog must be aligned with the applications’ criticality. An initiative with three levels of criticality can extend the table of criticality with an extra column to indicate the service catalog applicable.

| How important is the application for the business? | Score | FrAppSec Service Catalog Level |

|---|---|---|

| Very important | 3 | Premium |

| Important | 2 | Intermediate |

| Not important | 1 | Minimum |

The Intermediate service catalog level in this example can be described as the middle ground between the minimum and maximum levels presented above. This can be done according to the organization’s needs as it is expected that a good percentage of the applications will be in this category.

The service catalog is an indication of what services to be performed for which application. Particular applications, especially the ones which are important from a business perspective will have specific needs. They can be used as a driver for the maturity model.

Putting it all together

Application security is a complex field. The following approach is to be understood in the context of the current framework and the paradigms described in it.

-

Perform inventory of the applications

-

Define the application security strategy based on the inventory and the business strategy

-

Build the taxonomy

-

Build the soft layer

-

Build the service catalog

-

Build and execute the hard layer

-

Execute the risk management activities

-

Build and execute the real world layer

-

Improve the maturity model

-

Repeat!

Supporting documentation and templates

Applications Inventory

System Criticality Interview

Secure Application Development Policy

- Security principles

- Security requirements

- Security features

- Secure coding standards

- Security standards

FrAppSec Development Process

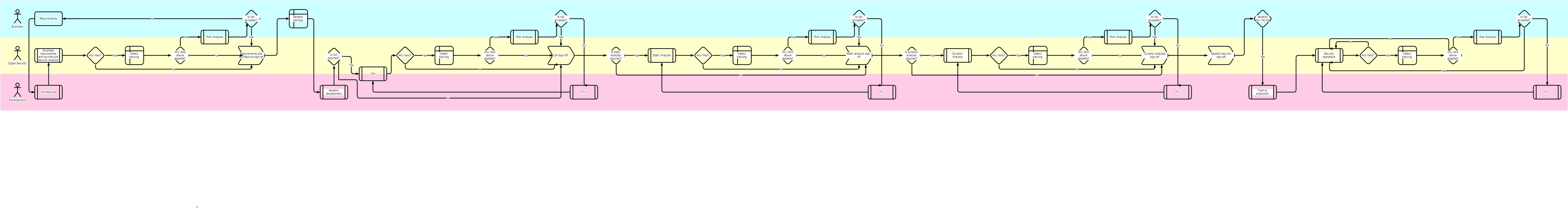

The proposed process covers three swimlanes across five major practices. Like everything else in this framework, it’s meant to be adapted to the needs of the organization. It’s not a project-like process with a clear beginning and ending. Other actors can be added, practices can be added or removed depending on the project. The process can be adapted to waterfall, agile and DevOps environments. The process is specific for each application (it applies to the “Application” paradigm in the taxonomy) even though multiple applications can share the same technology stack for the practices (it is actually recommended to reuse and simplify the technology stack). In fast paced environments it’s crucial to have a well engineered process and use automation to avoid delays caused by human interaction where this is not necessary.

RACI matrix for activities

Risk assessment form

Standard architectural descriptions

Useful and referenced links

https://www.owasp.org/index.php/OWASP_Risk_Rating_Methodology

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Risk_management